Phantom Attractions

Zoe Beloff, Dorothy F. Foster, Todd Hamel, Megan Mi-Ai Lee, Hanna Rochereau

Astor Weeks, New York, NY

June 27 - August 1, 2025

At the turn of the 20th century in the United States, urban reform initiatives that sought to inspire collective notions of beauty and civic pride through the establishment of monumental parks and museums were undermined by a new type of social space: the realm of commercial amusements. Theme parks, magic shows, and other popular attractions contrasted sharply with edifying kinds of leisure, offering visitors emotional and sensory experiences grounded in pleasure and spectacle. While these spaces derived exhibitionary strategies from public museums, they gave rise to accessible, vernacular forms easily translated into commodities. These expressions and their attendant devices of enchantment and allure constitute the basis of this exhibition.

The works on view draw on emotionally-charged cultural artifacts and sites, especially those whose capital is built on economies of hope and desire. They are presented as archives, drawings, and sculptures whose subjects range from consumer displays and manifestations of the subconscious to visionary attractions, fairground amusements and magic tricks. In her Theory of the Gimmick, Sianne Ngai proposes that such seemingly trivial vernacular forms can illuminate capitalism’s distortions, specifically its tendency to obscure labor, inflate value, and manipulate perceptions of time.

Zoe Beloff (b. 1958, Edinburgh, Scotland) is an artist and filmmaker who lives and works in New York City. Her projects often begin with historical research conducted both in institutional archives and through observations made in everyday spaces like city streets or while browsing flea markets. Drawn to anonymous and overlooked artifacts, Beloff channels detailed narratives to reanimate these histories as living documents that shed light on the present moment. These narratives—both real and imagined—form the foundation of her films, books, installations, performances, and exhibitions.

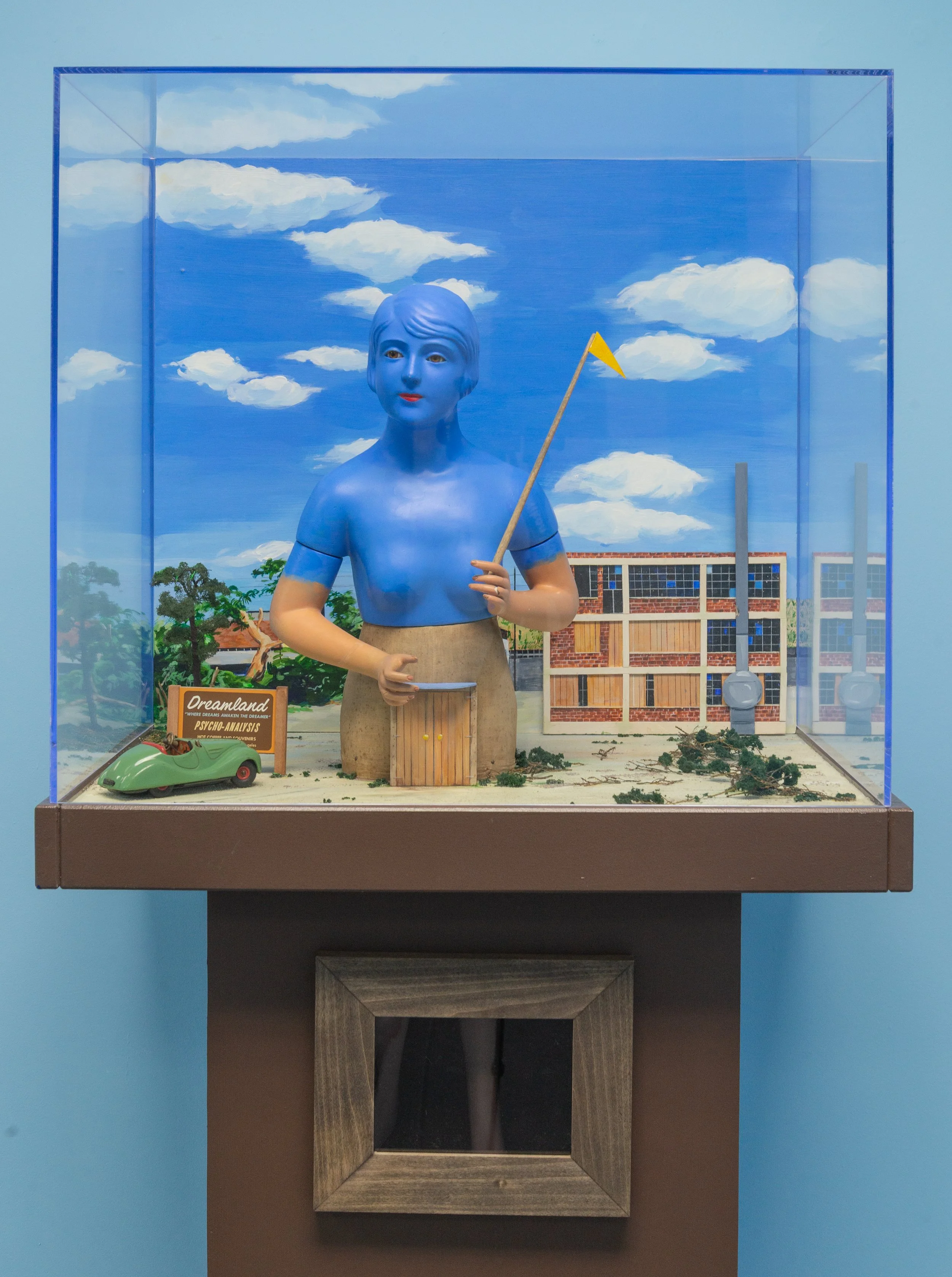

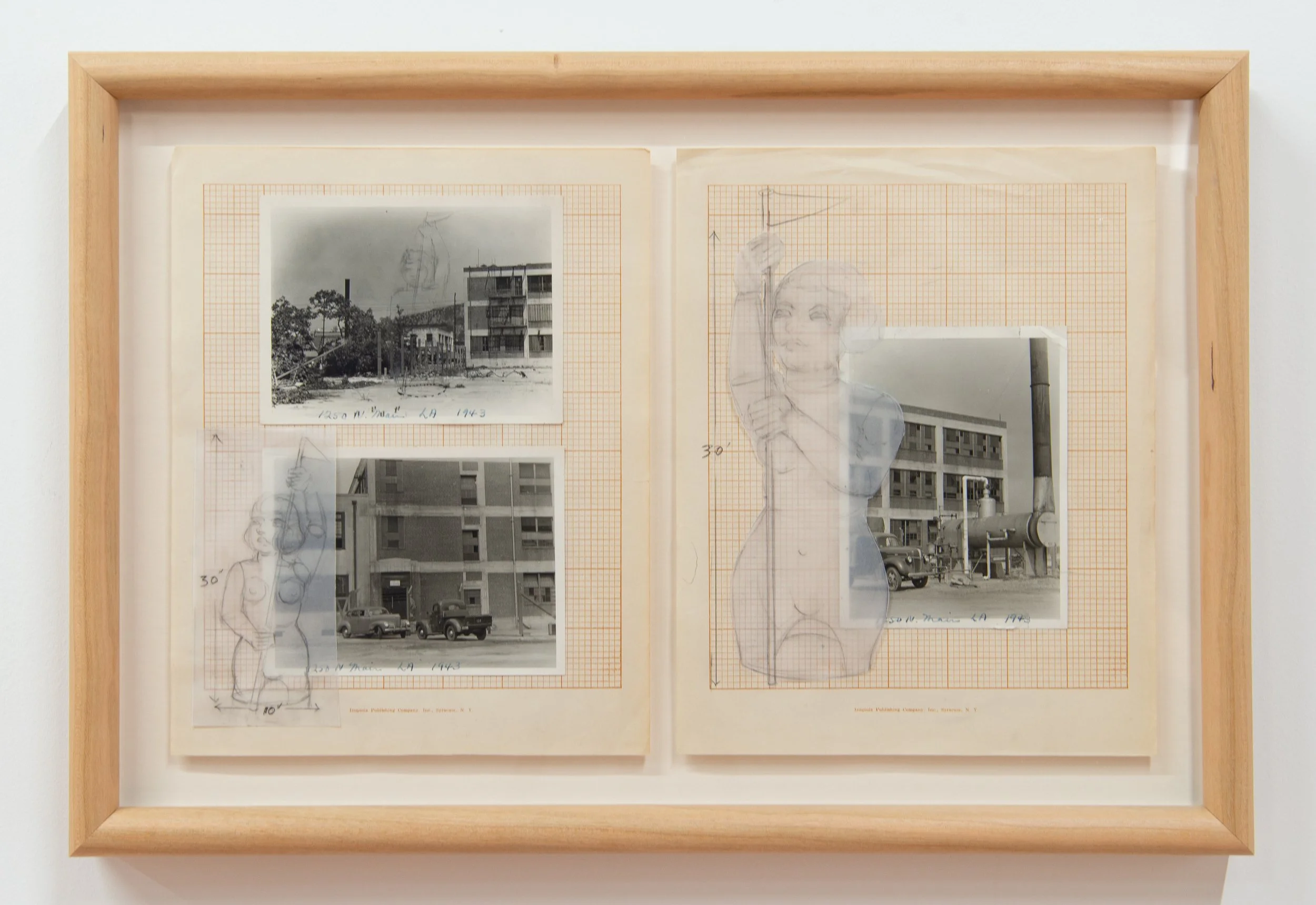

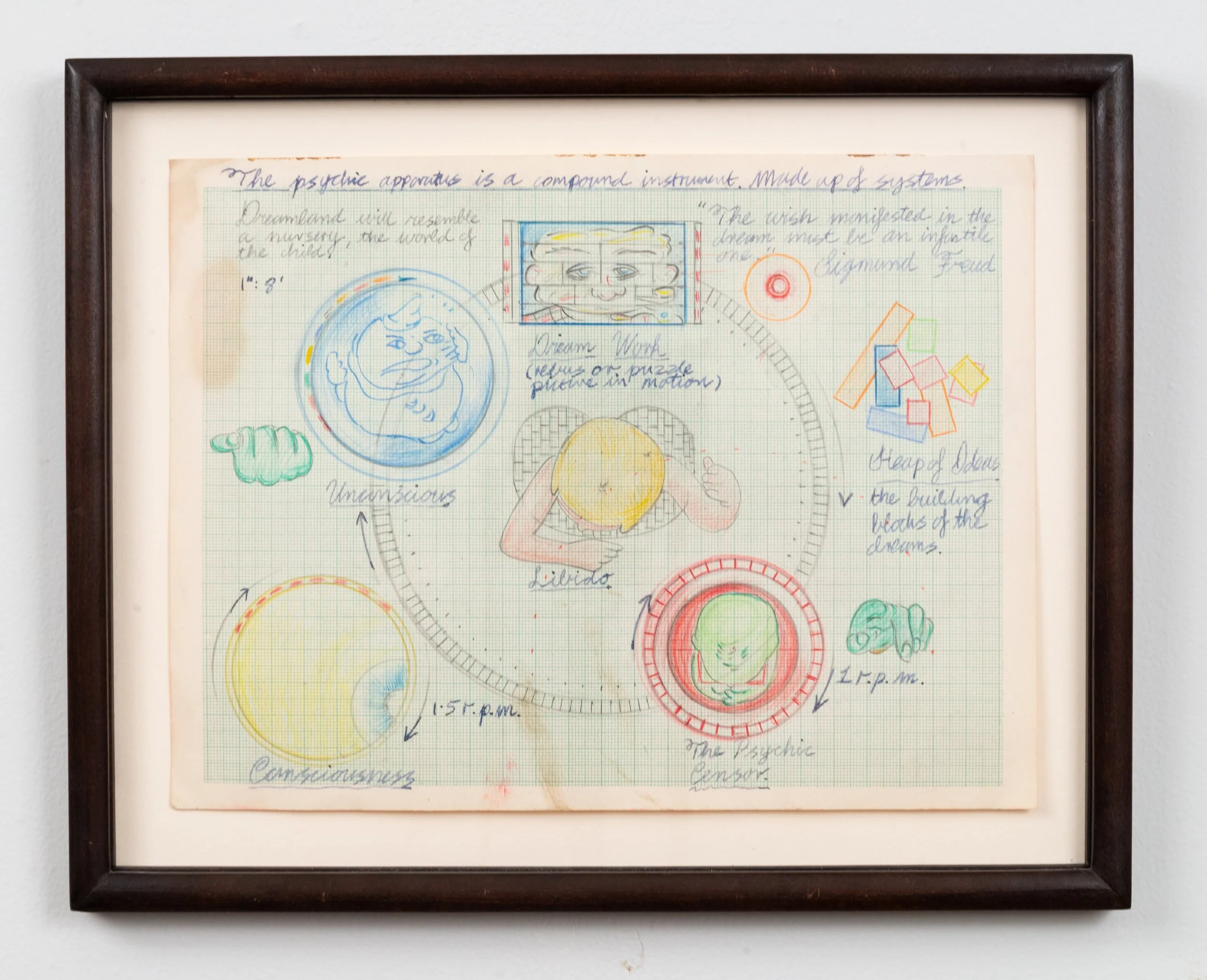

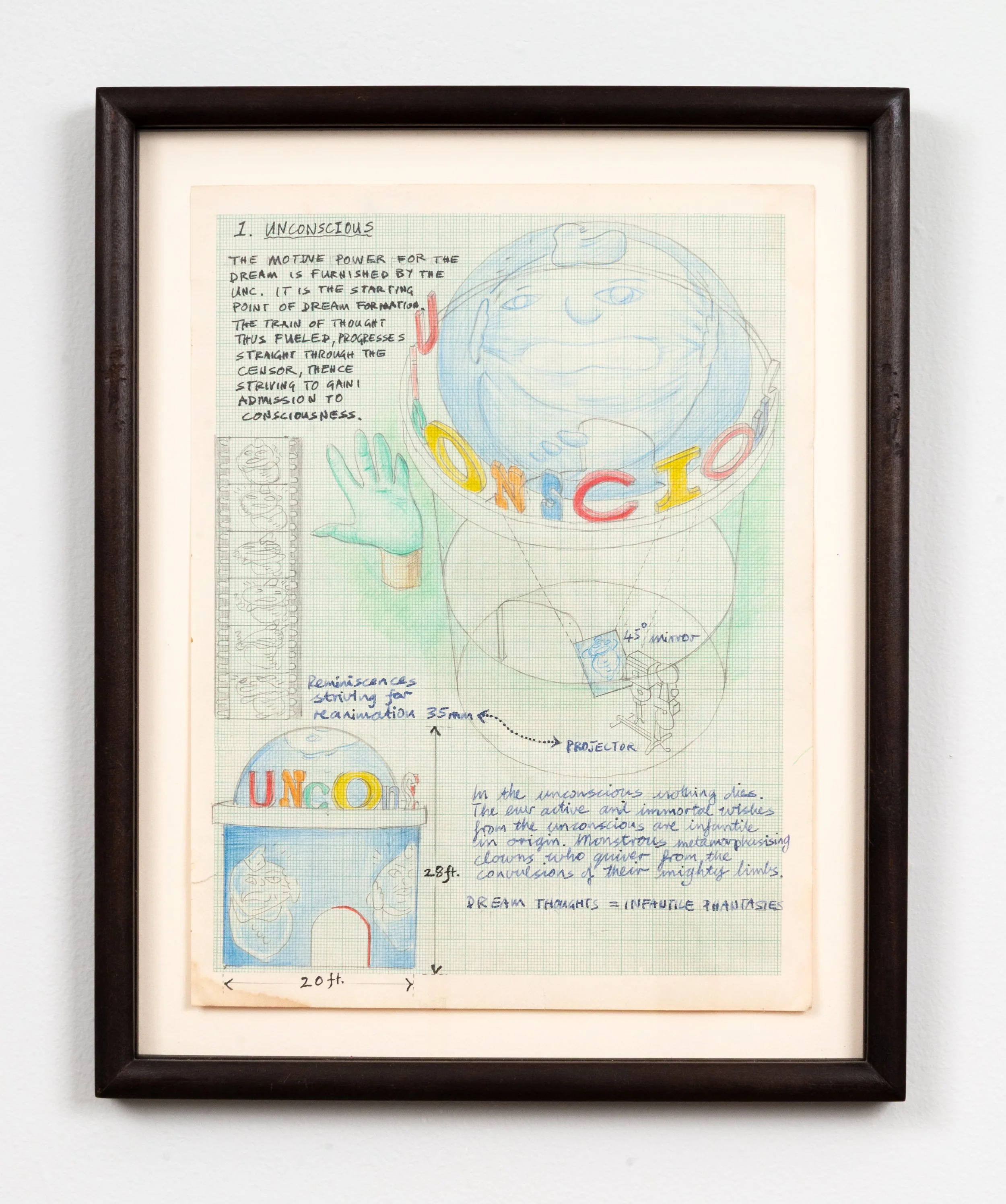

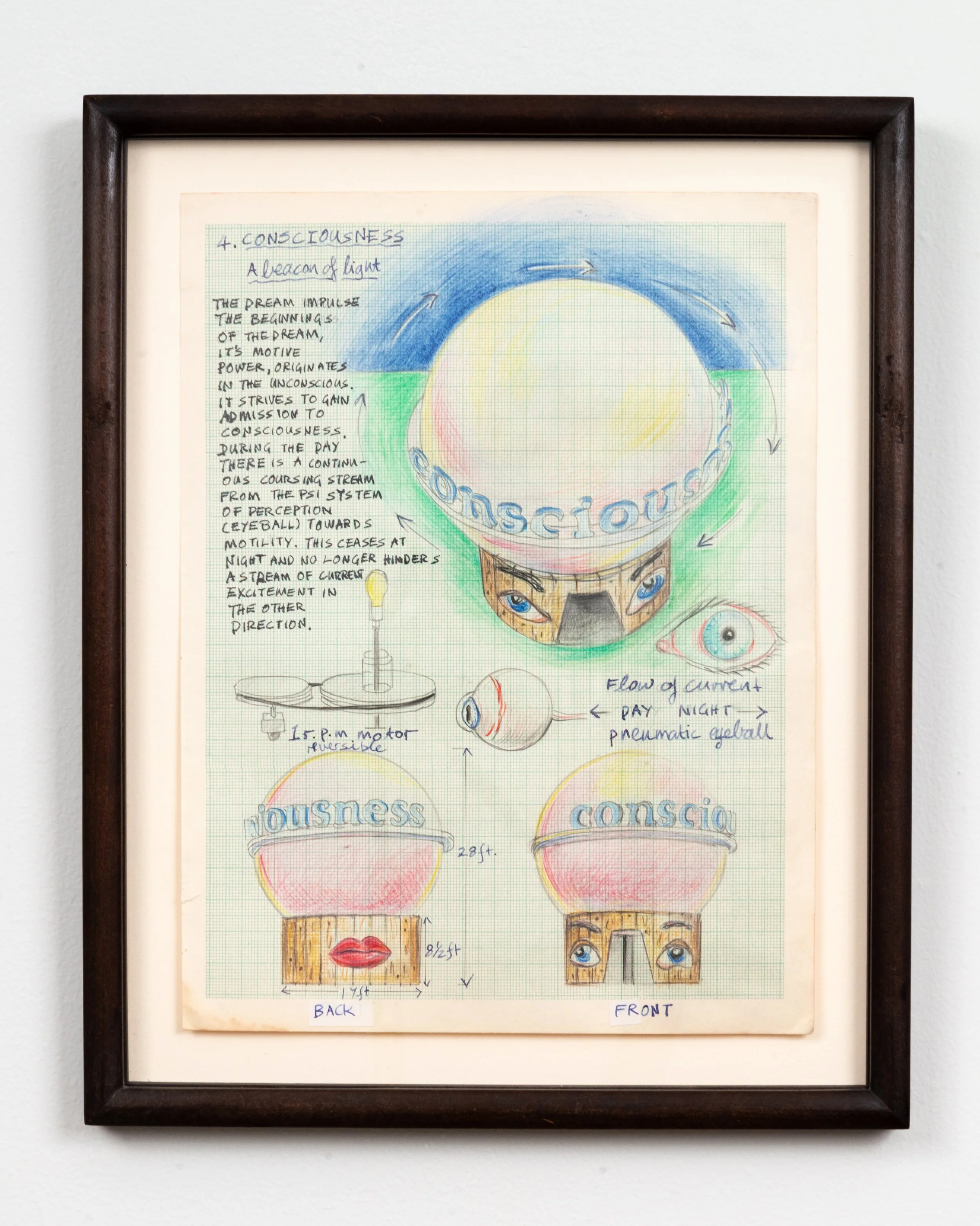

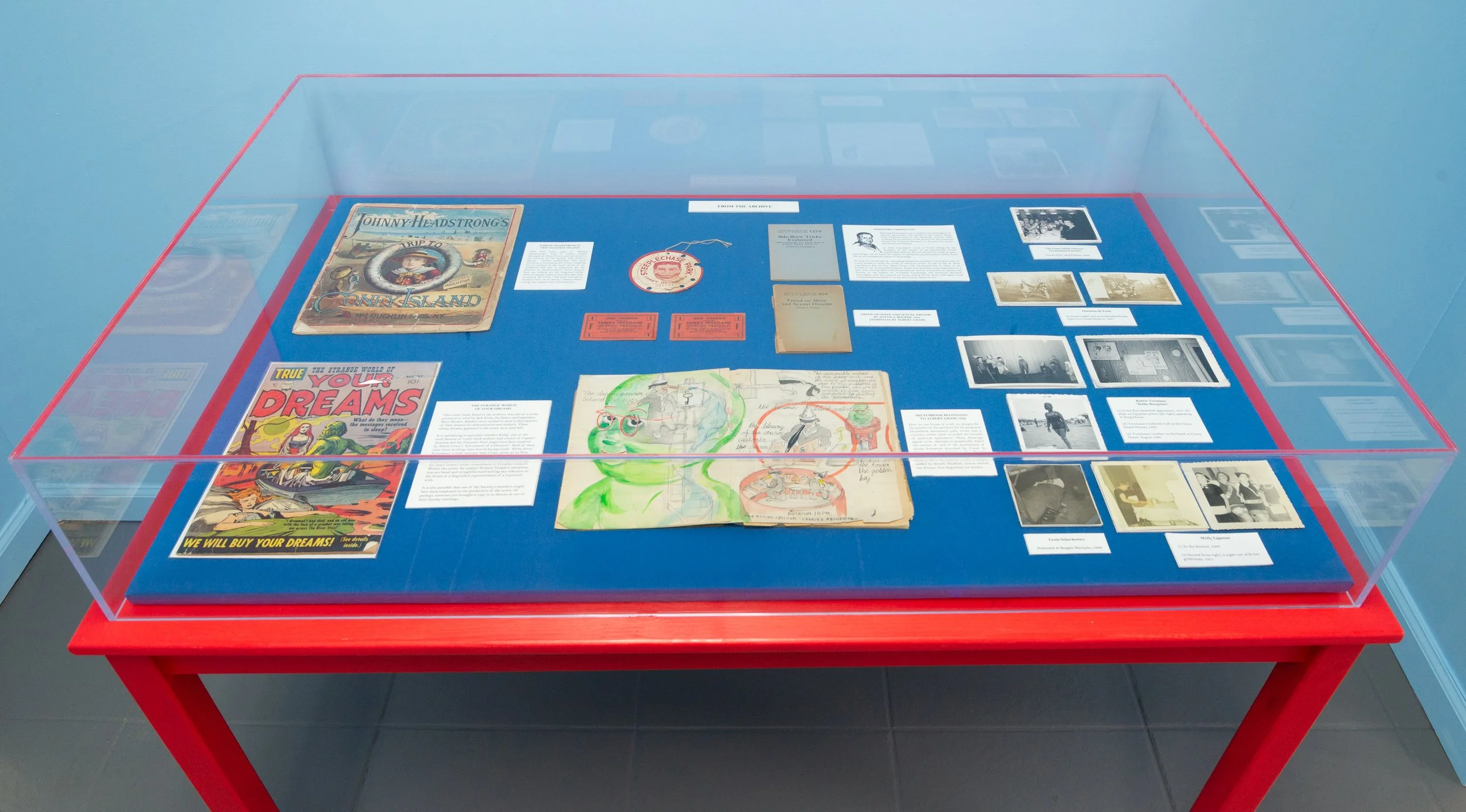

Among her best-known works is The Coney Island Amateur Psychoanalytic Society—an imagined collective of visionary filmmakers from the 1930s founded by Albert Grass, who Beloff describes as an alter ego. For this extensive project, Beloff created a fictional archive, selections of which are on view in this exhibition. These include the unrealized plans for Grass’s Dreamland (1930), a Coney Island amusement park based on Freud’s psychoanalytic theories, as well as Drive-In Dreamland, a novelty building designed for drive-by psychoanalysis sessions. The installation combines the artist’s own drawings and constructions with found historical documents, collections of photographs and other material traces of history.

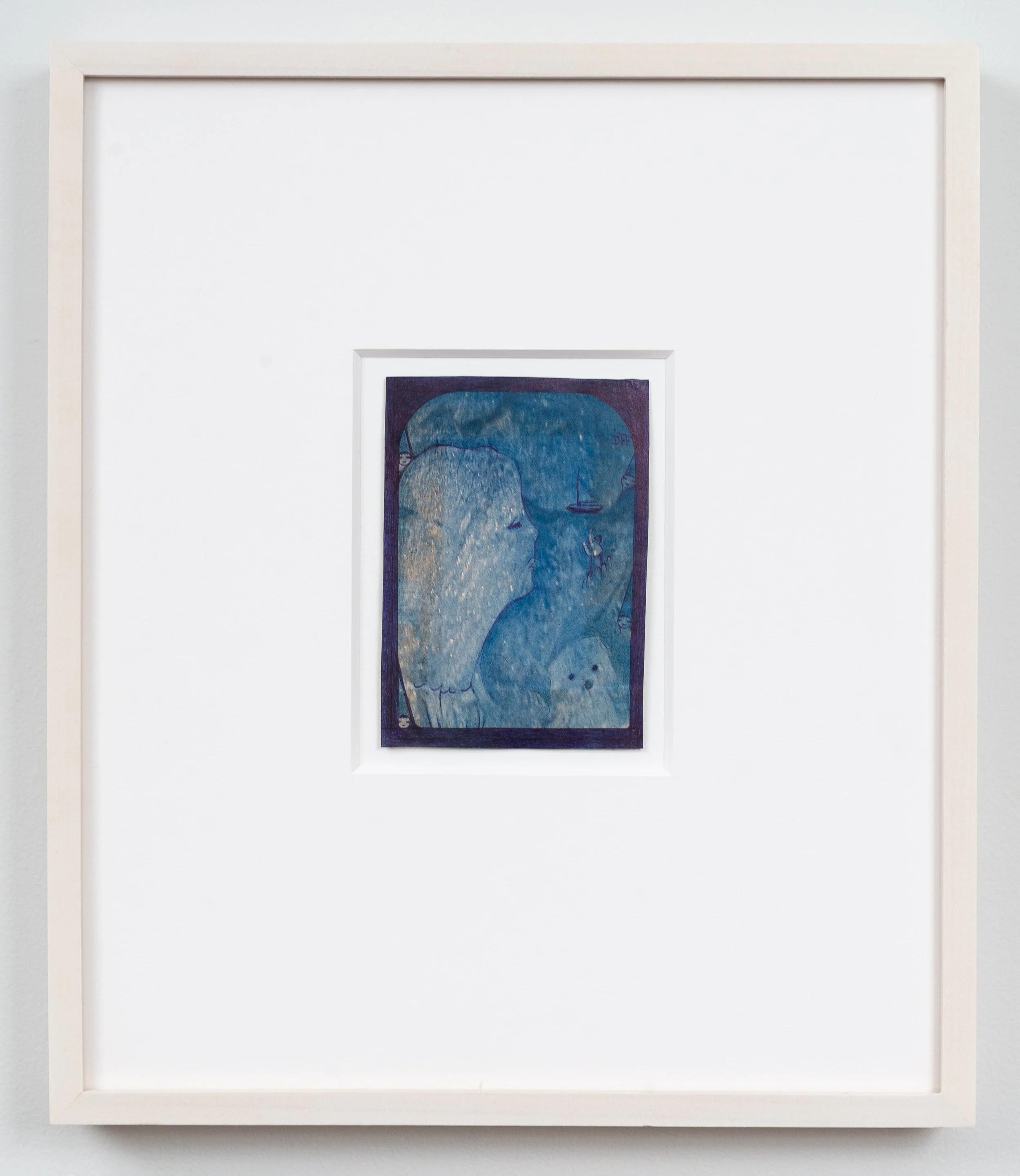

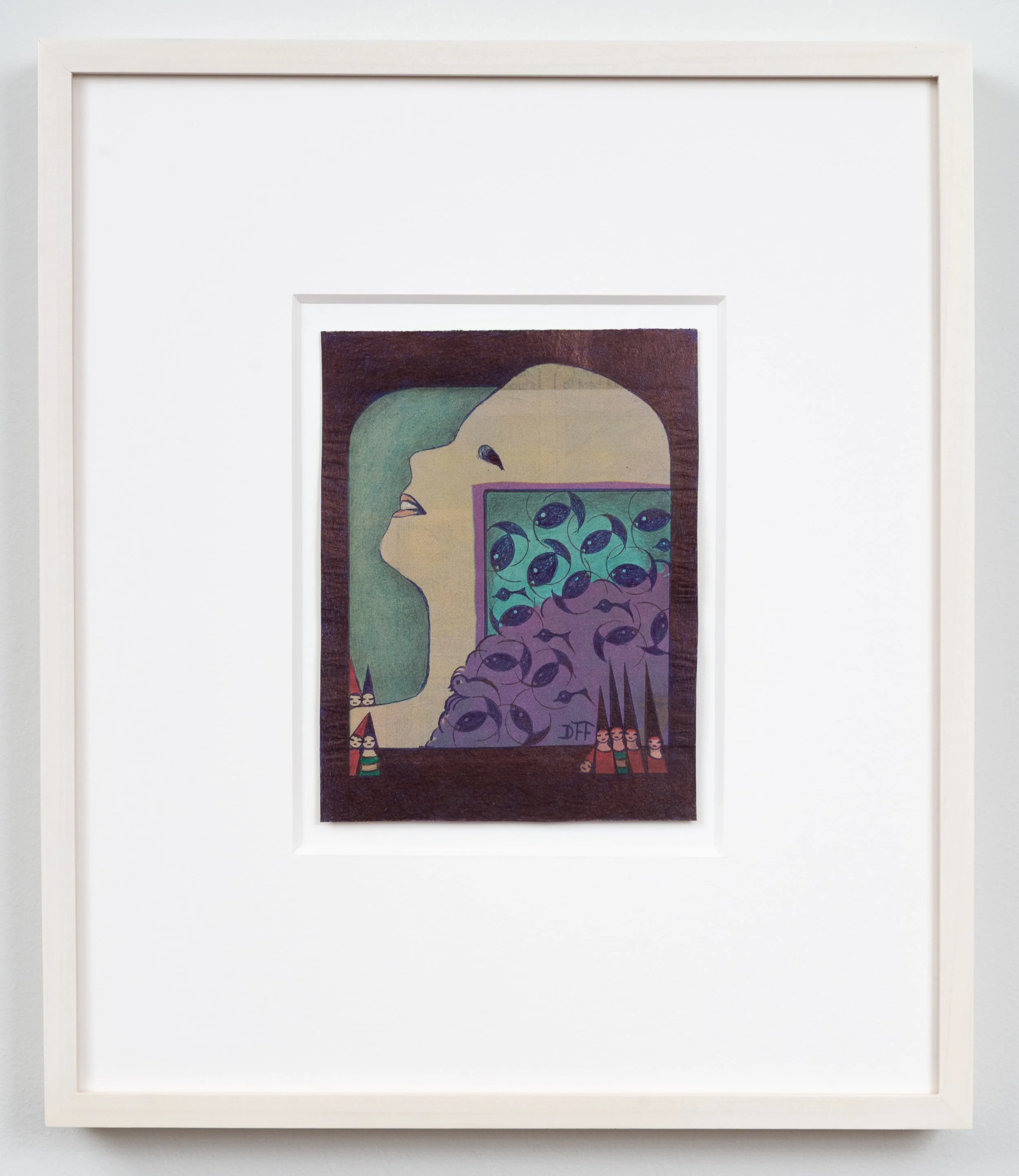

Dorothy F. Foster (1903–1986, b. Jersey City NJ; d. Port Jervis, NY) was a textile designer, artist, poet and memoirist who lived and worked in Manhattan. When she died in 1986, she left behind a significant corpus of unexhibited work: intimate drawings on trimmed pieces of magazines and newspapers, a selection of which is presented here. Using colored pencils and ballpoint pens in their professional range of colors - black, green, red and blue - Foster conjured strange, dreamlike scenes out of the printed photographs and graphics on each page, populating them with ghostly profiles of women, animal figures, and geometric patterns. Uniquely titled, her interventions range in style from commercial illustrations to cartoony doodles, and often emerge from the edges or contours of things like fabric folds or a mountainous landscape.

Foster’s life corresponded with the rising influence of psychoanalysis, which significantly reshaped ideas of selfhood and subconscious influence. She produced most of her surviving work during the final 15 years of her life while living in senior housing. In 1971 she wrote an experimental, stream-of-consciousness autobiography: “The Noisome Day / The Stilly Night” which tumbles back and forth across her life and reality to chronicle daily experiences, dreams, and vibrant social life with women in the city during its transformation to modern consumer culture. Poetic descriptions of cyclical dreamlike or subconscious states appear throughout the fragmented, time-traveling narrative: “Daydreams seem to collide with facts…to come up breathless with something bright and lively, patchwork droll, and yet a whole new-patterned, conjured-into-being thing.” (1) For Foster, the space of dreams and imagination became generative channels for producing work and accessing a liberated sense of self beyond social and temporal limits.

Todd Hamel (b. 1963, New Britain, CT) lives and works in Cheshire, CT. From 1989 to 1992 he owned and operated Roundabouts LTD, a company that specialized in hand-carved carousel horses, which he ran with the help of his brother, Kurt. Although the company has ceased regular operations, Hamel maintains an archive of patterns and partial forms in various states of completion—from horse manes, tails, legs, and heads to parts of menagerie animals—a selection of which is on view in this exhibition.

These fragments bear register marks, labels and conjoined limbs— vestiges of the manual technologies traditionally used in their construction. To assist in the laborious process of hand-carving, carousel craftsmen would often begin by roughing out shapes with a carving duplicator, a manual machine that dates back to 1915. Handcarved patterns served as guides for copying parts, and carvers would often join several patterns together in a line so that multiple limbs could be reproduced at once.

Prior to starting his own company, Hamel worked as a craftsman for Carousel Works Inc. in Mansfield OH, restoring historic carousels and figures created by well-known carvers. The tradition of carousel horse carving dates to mid-19th century Germany, and was popularized in the United States during the turn of the century when wooden carousels became the main attraction in amusement parks and fairs. After the Great Depression, carved wooden figures were largely replaced by fiberglass versions. Hamel studied illustration at the Paier College of Art in Hamden, CT.

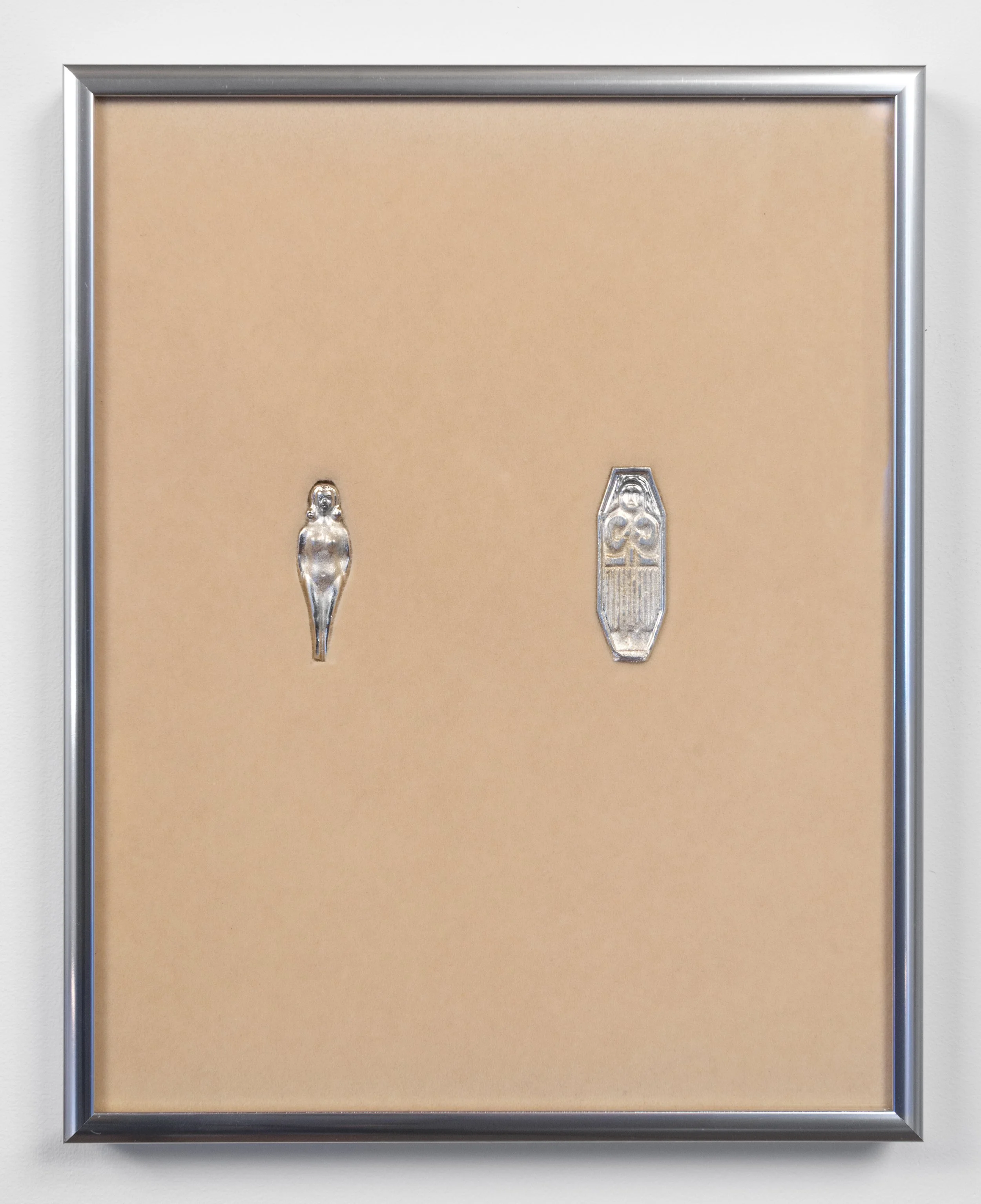

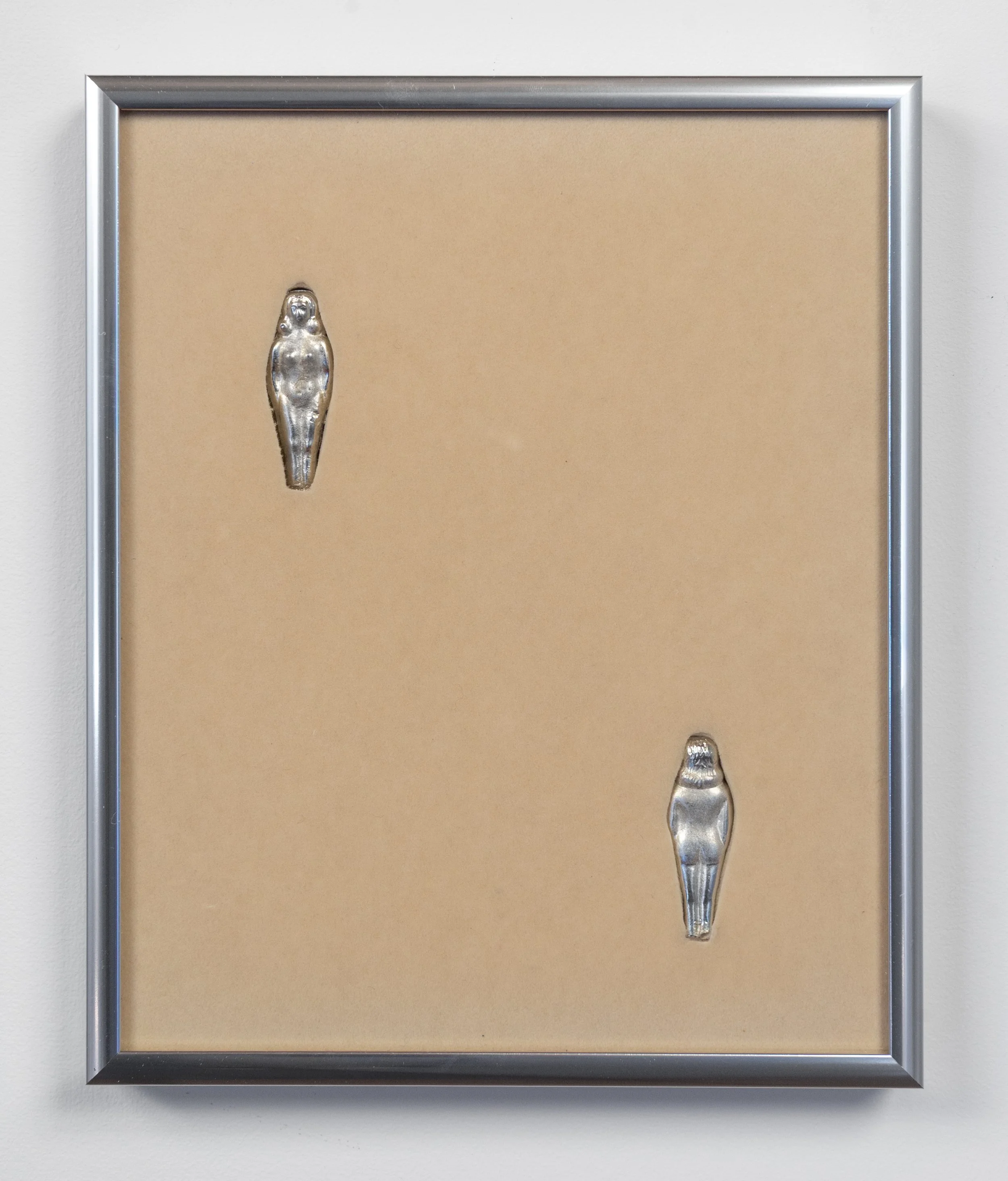

Megan Mi-Ai Lee’s (b. 1996, Los Angeles, CA, lives and works in Queens, NY) source material often includes souvenirs, magic tricks, signage, and props—ephemera she researches and collects from places like the Las Vegas Strip, where she spent time growing up. In her Zig Zag Girl series, a group of flattened cutouts lean against the wall, their stylized outlines of feminized bodies posed in various colorways. These abbreviated silhouettes are based on a classic stage trick in which a magician appears to slice his assistant into thirds. Another series features velvet and metal frames that house tiny nude or entombed female figures cast from the “Blonde in Bathtub” pocket trick, a novelty that involves placing a woman in either a bathtub or grave, depending on the version. Lee gives these talismanic objects ‘it-girl’ subtitles like Best Self, Every Day, and Living and Working. Across both bodies of work, Lee engages conventions used to display works of art—the museological vitrine, the minimalist object propped against the wall—devices that signal a certain mythology or aura. Attuned to the aesthetics of shorthand favored by capitalist systems, Lee calls attention to the ways in which abbreviations of gender and grandeur become stand-ins for value.

Hanna Rochereau’s (b. 1995, Paris, FR, lives and works in Marseille, FR) paintings and sculptures examine lifecycles of consumption through its material packaging. Weighing the excessive aesthetics of display against the austerity of storage, she explores how systems of value feed on our emotional investment. For two sculptures on view, Rochereau reproduces the showy trappings of commercial displays with tiered assemblages of discarded acrylic forms, velvet-lined boxes, jewelry busts, and mirrors—each bearing marks of repeated use beneath curls of silvery ribbon. If these sites normally rely on the illusory effects of cheap materials to elevate value and pique visual interest, Rochereau’s empty constructions emphasize the material futility of these housings.

In her recent paintings, Rochereau focuses on the storage rooms of commercial spaces: shadowy crevices of closets and shelves stacked with tightly-sealed boxes and packages. She renders these flat geometric components with thick applications of paint, occasionally integrating trompe l'oeil elements like labels, tape, and paper—references to the archive or library. These boxes might host the effects of one’s life, or the contents of an online purchase. One such painting on view articulates the cool folds of paper packaging, while a stamped date subtly encrypts a personal detail - the date of a friend’s birthday.

Zoe Beloff

Model for Drive-In Dreamland by Albert Grass (c. 1945), 2012

Wood, paint, plexiglass, found objects

67 × 27 5⁄16 × 19 3⁄8 inches

Zoe Beloff

Drawing for Drive-In Dreamland by Albert Grass, 1943, 2012

Colored pencil, ink and graphite on found paper

16 x 10 5/8 inches (framed)

Zoe Beloff

Drawing for Drive-In Dreamland by Albert Grass (Blue Sky Version), 1943, 2012

Colored pencil, ink and graphite on found paper

10 5⁄8 × 16 inches (framed)

Zoe Beloff

Drawing for Drive-In Dreamland (Merchandise) by Albert Grass, 1943, 2012

Colored pencil, ink and graphite on found paper

10 5⁄8 × 16 inches (framed)

Zoe Beloff

Drawing for Drive-In Dreamland (Site) by Albert Grass (c. 1945), 2012

Found photographs, vellum, and graphite on found paper

13 1⁄4 x 19 1⁄2 inches (framed)

Zoe Beloff

Plan of Dreamland pavilions by Albert Grass, 1930, 2009

Colored pencil, ink and graphite on found paper

10 1⁄4 x 12 3⁄4 inches (framed)

Zoe Beloff

Elevation of the “Unconscious” pavilion by Albert Grass, 1930, 2009

Colored pencil, ink and graphite on found paper

12 3⁄4 x 10 1⁄4 inches (framed)

Zoe Beloff

Elevation of the “Dream Work Factory” pavilion by Albert Grass, 1930, 2009

Colored pencil, ink and graphite on found paper

12 3⁄4 x 10 1⁄4 inches (framed)

Zoe Beloff

Elevation of the “Psychic Censor” and “Libido” pavilions by Albert Grass, 1930, 2009

Colored pencil, ink and graphite on found paper

12 3⁄4 x 10 1⁄4 inches (framed)

Zoe Beloff

Elevation of the “Consciousness” pavilion by Albert Grass, 1930, 2009

Colored pencil, ink and graphite on found paper

12 3⁄4 x 10 1⁄4 inches (framed)

Megan Mi-Ai Lee

Zig Zag Girl #3, 2025

Acrylic paint on wood

72 x 18 1⁄2 inches

Megan Mi-Ai Lee

Zig Zag Girl #4, 2025

Acrylic paint on wood

72 x 18 1⁄2 inches

Todd Hamel

Carved carousel components, c. 1989-1992

wood

dimensions variable

Todd Hamel

Carved carousel component, c. 1989-1992

wood

Todd Hamel

Carved carousel component, c. 1989-1992

wood

dimensions variable

Megan Mi-Ai Lee

Blonde in Bathtub (Living and Working), 2025

Pewter, velvet, foam

9 1⁄2 x 7 1⁄2 inches

Dorothy F. Foster

“Ocean Grove” N.J., c. 1970-86

Ballpoint pen on found coated newsprint

Unframed: 6 1⁄8 x 4 1⁄4 inches (Framed: 14 3⁄4 x 12 3⁄4 inches)

Dorothy F. Foster

True Blue (Dream), c. 1970-1986

Ballpoint pen on found newsprint

Unframed: 5 1⁄8 x 3 5⁄8 inches (Framed: 14 3⁄4 x 12 3⁄4 inches)

Dorothy F. Foster

“Cave” (In Deep Woods), c. 1970-1986

Ballpoint pen, colored pencil, and graphite on found paper

4 3⁄4 x 5 1⁄4 inches (Framed: 14 3⁄4 x 12 3⁄4 inches)

Hanna Rochereau

Boxes in boxes 17, 2025

mirror, mdf, acrylic, ribbon, cardboard, velvet, plastic

11.75 x 9.4 x 10.6 inches (30 x 24 x 27 cm)

Dorothy F. Foster

Issue, c. 1970-1986

Ink on found printed paper

4 x 5 3⁄8 inches (Framed: 14 3⁄4 x 12 3⁄4 inches)

Megan Mi-Ai Lee

Zig Zag Girl #5, 2025

Acrylic paint on wood

72 x 22 inches

Hanna Rochereau

Boxes in boxes 18, 2025

ribbon, cardboard, plastic

7 x 6.3 x 6.3 inches (18 x 16 x 16 cm)

Megan Mi-Ai Lee

Blonde in Bathtub (Every Day), 2025

Pewter, velvet, foam

7 1/2 x 5 1/2 inches

Dorothy F. Foster

Pet Acquires Pet Shop, c. 1970-1986

Ballpoint pen and colored pencil on found coated newsprint

6 3⁄4 x 5 1⁄8 inches (framed: 14 3⁄4 x 12 3⁄4 inches)

Dorothy F. Foster

Honeymoon Suite, c. 1970-1986

Ballpoint pen on found, coated newsprint

4 3⁄4 x 5 1⁄4 inches (framed: 14 3⁄4 x 12 3⁄4 inches)

Megan Mi-Ai Lee

Blonde in Bathtub (Best Self), 2025

Pewter, velvet, foam

8 x 6.5 inches

Hanna Rochereau

11.11, 2025

acrylic on canvas

12.5 x 12.5 inches (32 x 32 cm)